about jeanne l. norbeck

Women Airforce Service Pilot (WASP), World War II

Information researched and written by Rod Lewellen, Jeanne's nephew, and Margaret Marnitz, Jeanne's niece.

Jeanne Marcile Lewellen was born in Columbus, Indiana, on November 14, 1912, to Darcy and Mayme Lewellen. She grew up in Columbus with her sister, Frances, and her brother, Emmons.

Jeanne graduated in 1929 from Columbus High School. She was active in Dramatic Club, Science Club, and Honor Society, and was the high School Yearbook Editor, the Junior and Senior Class Secretary and May Queen.

She was a member of the First Christian Church in Columbus.

She graduated in 1933 with honors from the State College of Washington at Pullman with a degree in English. She was active in Quill Club and Panhellenic Council and was a member of Phil Kappa Phi honorary scholastic society and Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority. She served as treasurer of the Mortar Board scholastic society. She was elected a ROTC Sponsor and she served as the Senior Woman Representative on the College Board of Control.

Jeanne became interested in flying while in high school and took some lessons during her senior year. She earned her pilot's license while in college. Some of the airplanes she flew were the Aeronca (65 hp), Piper Cub (65 hp), and Piper Cub Cruiser (75 hp).

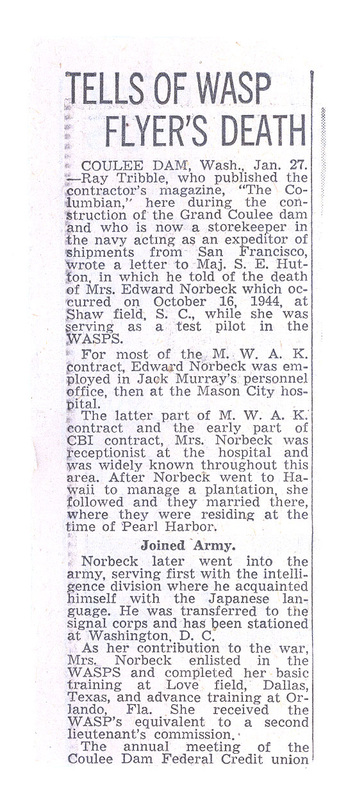

For four years after college, Jeanne worked as secretary to the Chief Surgeon of the Grand Coulee Dam construction site hospital in Washington State. She was one of the few women in that wilderness area who witnessed the progress of this monumental project.

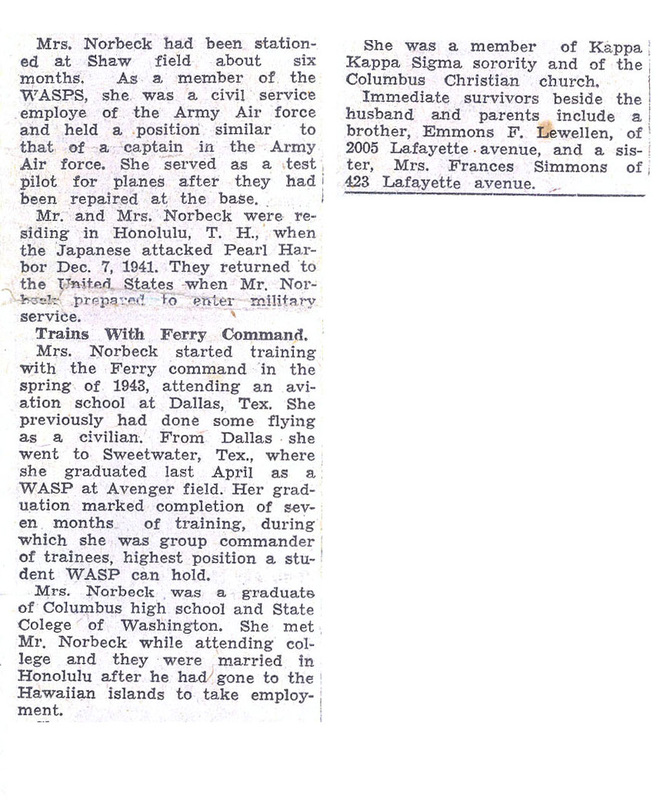

Jeanne met Edward Norbeck when she worked at the Grand Coulee Dam project. Edward was the office manager at the construction headquarters. They were married on September 22, 1940, in Wahiawa, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii. They were home in Honolulu on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor just a few miles from their house. For the next fifteen months, they both served in Honolulu as voluntary air raid wardens. In March 1943, Edward entered the U.S. Army Intelligence Service and Jeanne returned to her family home in Columbus. With her husband in the Army, Jeanne wanted to do her part by putting her flying ability to use for the war effort. After completing additional pilot training at the Dallas Aviation School and the Roscoe Turner Aviation School, she applied for the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). She had a total of 35 1/2 hours of flying time. In October 1943, Jeanne entered the WASP training program in class 44-W-3 at Avenger Field, Sweetwater, Texas. There were 100 cadets enrolled in class 44-W-3 - and of these, 53 washed out and 57 graduated.

Except for combat training, Jeanne completed the same course of classroom study, flight instruction and check flights, and flew the same military airplanes as Army Air Force cadets. She flew the Fairchild PT-19A (175 hp) primary trainer, the Boeing-Stearman PT-17A (220 hp) primary trainer, the Vultee BT-13 (450 hp) basic trainer, and the North American AT-6 (600 hp) advanced trainer.

Jeanne was appointed Group Commander of her training class, the highest position a WASP cadet could hold. She graduated on April 15, 1944, becoming one of the 1,074 women pilots who earned their WASP wings.

After graduation, Jeanne was selected to attend a special WASP officer's training course at the Army Air Force Tactical Center at Orlando, Florida. She went to Orlando after her graduation and successfully completed the course on May 12, 1944.

Jeanne was assigned to Shaw Field, Sumter, South Carolina, and reported for duty on May 16, 1944, as an Engineering Test Pilot. Her job was to fly "red-lined" Army Air Force trainers to analyze problems needing repair and write engineering reports for the maintenance department. She also flew repaired trainers, putting them through rigorous flying tests to make certain they were safe for instructors and cadets to fly. The planes she tested at Shaw Field were the Vultee BT-13 and BT-15 basic trainers, the North American AT-6 advanced trainer, and the Beechcraft AT-10 twin engine advanced trainer.

By 1944, most of the engineering test flying at training bases was done by the WASP, which freed male pilots from this dangerous job and made them available for instructor or combat duty. The WASP were part of the Civil Service, so Jeanne did not have an army officer's commission, pay, or benefits. She lived in the Women Army Corps (WAC) officer's quarters at Shaw Field and worked ten hours a day, six days a week, with time off on Sunday.

On Saturday, October 7, 1944, Jeanne got the weekend off and hitched a ride on an Army Air Force plane to Atterbury Army Air Field at Columbus to visit her family. She remained overnight and hitched a ride back to Shaw Field, Sumter, South Carolina late Sunday afternoon.

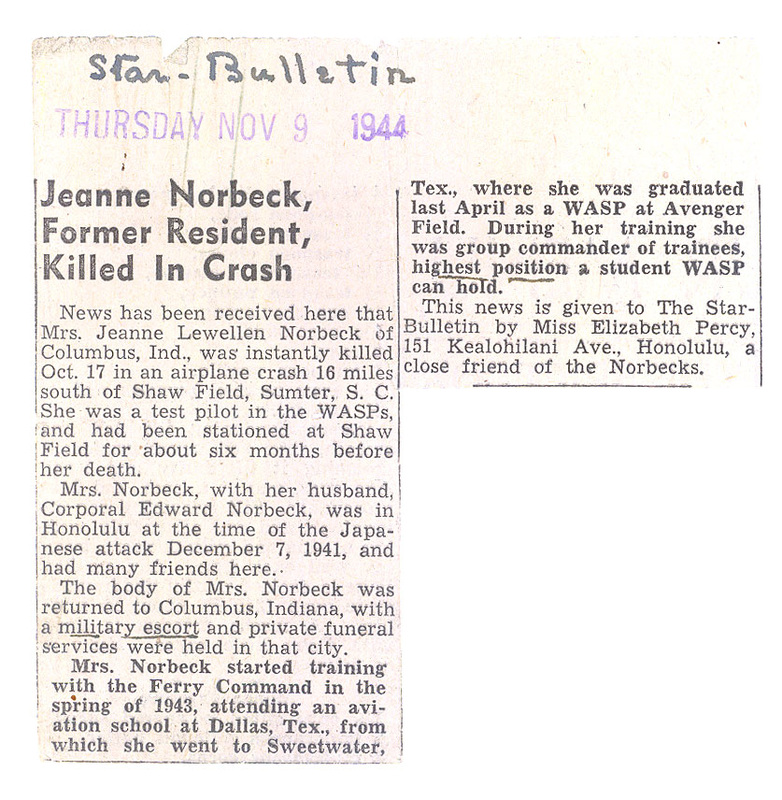

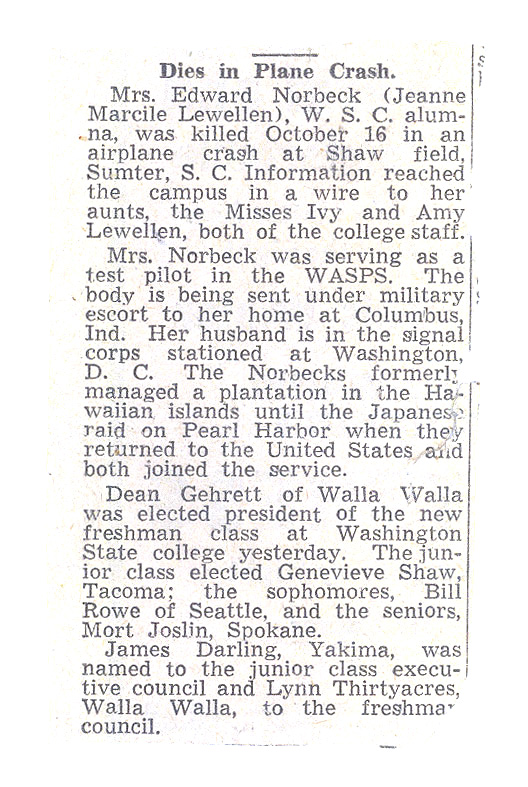

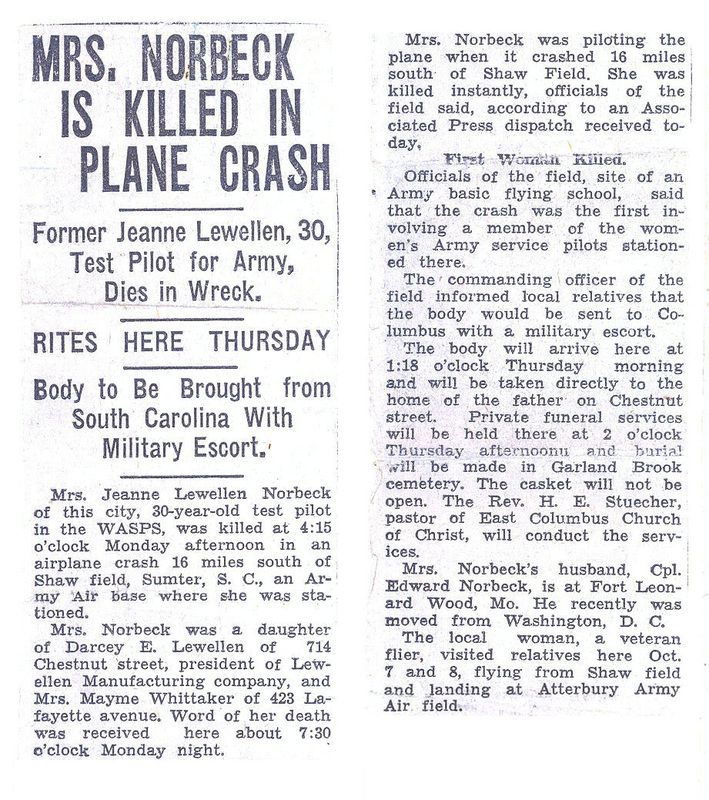

On the afternoon of Monday, October 16, 1944, Jeanne and a WASP friend, Marybelle Lyall Arduengo, reported for their next test assignments. On the line were two BT-13 trainers. They flipped a quarter to see which airplane each would test. The BT-13 that Jeanne got in the coin toss had been red lined with a possible structural problem in the left wing. Jeanne and Marybelle took off one after the other and flew together to the test area south of Shaw Field, communicating by radio. Jeanne told Marybelle that her BT-13 seemed to be all right in straight and level flight. When they arrived at the test area, they separated and flew to different locations for their tests. Marybelle did not hear from Jeanne again on the radio.

Shortly after they split up, Jeanne had apparently discovered that something was definitely wrong with the wing. She was turning back toward the base when the plane suddenly rolled over and went into a spin. At the assigned approach altitude of 500 feet, there was nothing Jeanne could do to regain control. The airplane crashed upside down and burned. The telegram reporting her death was delivered to her father's house at 7:30 pm the same day.

An Army Air Force officer escorted Jeanne's casket to Columbus. He brought with him an American flag that was placed on her casket. Marybelle Lyall Arduengo flew a North American AT-6 from Shaw Field to Columbus to represent the WASP. Jeanne's husband, Edward, who was in an intelligence training course at Fort Leonard Wood, received a special pass and priority travel vouchers, and arrived in time for the funeral. Jeanne was buried in Garland Brook cemetery in Columbus, Indiana.

In the October 18, 1944, issue of the Columbus, Indiana newspaper, The Evening Republican, a columnist wrote, "Mrs. Norbeck died in the line of duty as clearly as any flier has. We do not find in the county's records another case where a woman's body had been returned here for burial with a military escort."

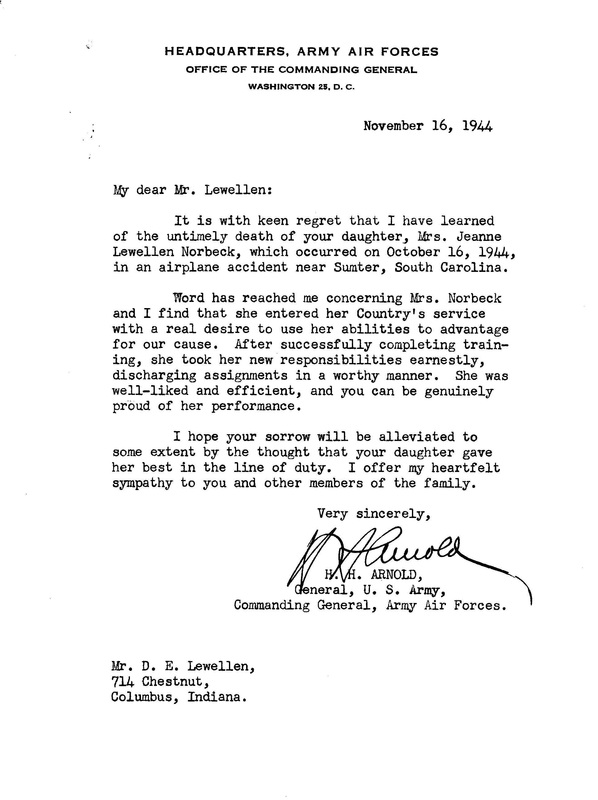

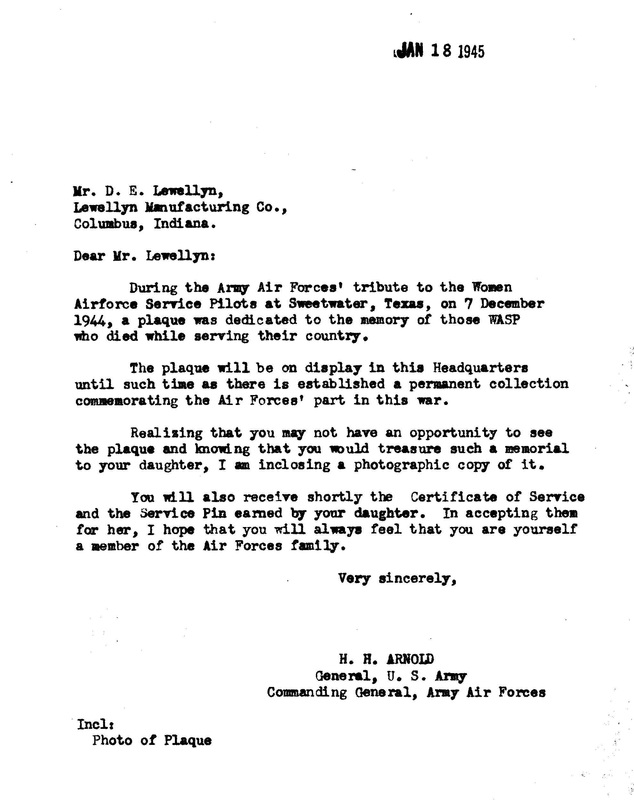

In November 1944, Jeanne's family received a letter signed by General H. H. Arnold, Commanding General, Army Air Forces, extending his sympathy. In January 1945, Jeanne's family received another letter (see both below) from General Arnold along with a photograph of the "In Memoriam" bronze plaque that he had personally dedicated on December, 7, 1944, at Avenger Field to the 38 WASP who were killed in the line of duty.

The same month, the president of the State College of Washington, Dr. E. O. Holland, sent Jeanne's father a framed certificate entitled, "In Grateful Tribute." The certificate indicated that her name had been added to the roll of the college Veterans Memorial in remembrance of her sacrifice. In October 1945, Dr. Holland sent a copy of the Archibald MacLeish poem, The Young Dead Soldiers. He suggested that it be kept with the framed certificate and read by the members of her family down through future generations as a way to remember her and the sacrifice she made for her country (see poem at end of this web page).

The February 1945 issue of the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority publication, The Key, carried an article about Jeanne announcing that she was the first member of the sorority to be killed in the service of her country in World War II.

Edward Norbeck survived the war and remarried (find out more about him below).

An account of Jeanne's fatal test flight can be found in:

Jeanne graduated in 1929 from Columbus High School. She was active in Dramatic Club, Science Club, and Honor Society, and was the high School Yearbook Editor, the Junior and Senior Class Secretary and May Queen.

She was a member of the First Christian Church in Columbus.

She graduated in 1933 with honors from the State College of Washington at Pullman with a degree in English. She was active in Quill Club and Panhellenic Council and was a member of Phil Kappa Phi honorary scholastic society and Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority. She served as treasurer of the Mortar Board scholastic society. She was elected a ROTC Sponsor and she served as the Senior Woman Representative on the College Board of Control.

Jeanne became interested in flying while in high school and took some lessons during her senior year. She earned her pilot's license while in college. Some of the airplanes she flew were the Aeronca (65 hp), Piper Cub (65 hp), and Piper Cub Cruiser (75 hp).

For four years after college, Jeanne worked as secretary to the Chief Surgeon of the Grand Coulee Dam construction site hospital in Washington State. She was one of the few women in that wilderness area who witnessed the progress of this monumental project.

Jeanne met Edward Norbeck when she worked at the Grand Coulee Dam project. Edward was the office manager at the construction headquarters. They were married on September 22, 1940, in Wahiawa, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii. They were home in Honolulu on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor just a few miles from their house. For the next fifteen months, they both served in Honolulu as voluntary air raid wardens. In March 1943, Edward entered the U.S. Army Intelligence Service and Jeanne returned to her family home in Columbus. With her husband in the Army, Jeanne wanted to do her part by putting her flying ability to use for the war effort. After completing additional pilot training at the Dallas Aviation School and the Roscoe Turner Aviation School, she applied for the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). She had a total of 35 1/2 hours of flying time. In October 1943, Jeanne entered the WASP training program in class 44-W-3 at Avenger Field, Sweetwater, Texas. There were 100 cadets enrolled in class 44-W-3 - and of these, 53 washed out and 57 graduated.

Except for combat training, Jeanne completed the same course of classroom study, flight instruction and check flights, and flew the same military airplanes as Army Air Force cadets. She flew the Fairchild PT-19A (175 hp) primary trainer, the Boeing-Stearman PT-17A (220 hp) primary trainer, the Vultee BT-13 (450 hp) basic trainer, and the North American AT-6 (600 hp) advanced trainer.

Jeanne was appointed Group Commander of her training class, the highest position a WASP cadet could hold. She graduated on April 15, 1944, becoming one of the 1,074 women pilots who earned their WASP wings.

After graduation, Jeanne was selected to attend a special WASP officer's training course at the Army Air Force Tactical Center at Orlando, Florida. She went to Orlando after her graduation and successfully completed the course on May 12, 1944.

Jeanne was assigned to Shaw Field, Sumter, South Carolina, and reported for duty on May 16, 1944, as an Engineering Test Pilot. Her job was to fly "red-lined" Army Air Force trainers to analyze problems needing repair and write engineering reports for the maintenance department. She also flew repaired trainers, putting them through rigorous flying tests to make certain they were safe for instructors and cadets to fly. The planes she tested at Shaw Field were the Vultee BT-13 and BT-15 basic trainers, the North American AT-6 advanced trainer, and the Beechcraft AT-10 twin engine advanced trainer.

By 1944, most of the engineering test flying at training bases was done by the WASP, which freed male pilots from this dangerous job and made them available for instructor or combat duty. The WASP were part of the Civil Service, so Jeanne did not have an army officer's commission, pay, or benefits. She lived in the Women Army Corps (WAC) officer's quarters at Shaw Field and worked ten hours a day, six days a week, with time off on Sunday.

On Saturday, October 7, 1944, Jeanne got the weekend off and hitched a ride on an Army Air Force plane to Atterbury Army Air Field at Columbus to visit her family. She remained overnight and hitched a ride back to Shaw Field, Sumter, South Carolina late Sunday afternoon.

On the afternoon of Monday, October 16, 1944, Jeanne and a WASP friend, Marybelle Lyall Arduengo, reported for their next test assignments. On the line were two BT-13 trainers. They flipped a quarter to see which airplane each would test. The BT-13 that Jeanne got in the coin toss had been red lined with a possible structural problem in the left wing. Jeanne and Marybelle took off one after the other and flew together to the test area south of Shaw Field, communicating by radio. Jeanne told Marybelle that her BT-13 seemed to be all right in straight and level flight. When they arrived at the test area, they separated and flew to different locations for their tests. Marybelle did not hear from Jeanne again on the radio.

Shortly after they split up, Jeanne had apparently discovered that something was definitely wrong with the wing. She was turning back toward the base when the plane suddenly rolled over and went into a spin. At the assigned approach altitude of 500 feet, there was nothing Jeanne could do to regain control. The airplane crashed upside down and burned. The telegram reporting her death was delivered to her father's house at 7:30 pm the same day.

An Army Air Force officer escorted Jeanne's casket to Columbus. He brought with him an American flag that was placed on her casket. Marybelle Lyall Arduengo flew a North American AT-6 from Shaw Field to Columbus to represent the WASP. Jeanne's husband, Edward, who was in an intelligence training course at Fort Leonard Wood, received a special pass and priority travel vouchers, and arrived in time for the funeral. Jeanne was buried in Garland Brook cemetery in Columbus, Indiana.

In the October 18, 1944, issue of the Columbus, Indiana newspaper, The Evening Republican, a columnist wrote, "Mrs. Norbeck died in the line of duty as clearly as any flier has. We do not find in the county's records another case where a woman's body had been returned here for burial with a military escort."

In November 1944, Jeanne's family received a letter signed by General H. H. Arnold, Commanding General, Army Air Forces, extending his sympathy. In January 1945, Jeanne's family received another letter (see both below) from General Arnold along with a photograph of the "In Memoriam" bronze plaque that he had personally dedicated on December, 7, 1944, at Avenger Field to the 38 WASP who were killed in the line of duty.

The same month, the president of the State College of Washington, Dr. E. O. Holland, sent Jeanne's father a framed certificate entitled, "In Grateful Tribute." The certificate indicated that her name had been added to the roll of the college Veterans Memorial in remembrance of her sacrifice. In October 1945, Dr. Holland sent a copy of the Archibald MacLeish poem, The Young Dead Soldiers. He suggested that it be kept with the framed certificate and read by the members of her family down through future generations as a way to remember her and the sacrifice she made for her country (see poem at end of this web page).

The February 1945 issue of the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority publication, The Key, carried an article about Jeanne announcing that she was the first member of the sorority to be killed in the service of her country in World War II.

Edward Norbeck survived the war and remarried (find out more about him below).

An account of Jeanne's fatal test flight can be found in:

- Byrd Howell Granger, On Final Approach: The Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II, Falconer Publishing Company, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1991

- Women Who Dared: American Female Test Pilots, Flight-Test Engineers, and Astronauts, 1912-1996, Lt. Col. Yvonne C. Pateman, Norstahr Publishing Company, California, 1997

Family photo with Jeanne, her brother, Emmons, her mother, Mayme, and her sister Frances, Summer 1933.

Jeanne Lewellen Norbeck's family members in this photograph of a play ship taken by Emmons Lewellen the summer of 1940, at his Columbus, Indiana home on Chestnut Street, just before Jeanne returned to Hawaii to marry Edward Norbeck in September. First row is Jeanne Lewellen, Mabel Lewellen, and Darcy Lewellen, Jeanne's father. In the second row is Frances Lewellen, Frances Simmons, and Margaret Simmons, Jeanne's sister. Rod Lewellen is standing at the wheel.

in honor of jeanne

In July 1995, an exhibit of some of Jeanne's WASP materials was dedicated at the Atterbury-Bakalar Air Museum at the Columbus Municipal Airport, Columbus, Indiana.

In May 1997, Jeanne's name was inscribed on one of the 25 columns of the Bartholomew County Memorial for Veterans on the lawn of the Bartholomew County Courthouse in Columbus, Indiana. Also inscribed on the memorial is an excerpt from a letter Jeanne had mailed to her mother the morning of the day she was killed.

In May 1998, the restored chapel in a WWII barracks at the Columbus Municipal Airport was named the Jeanne Lewellen Norbeck Memorial Chapel and dedicated to her memory.

In June 1999, Washington State university featured an article about Jeanne in its paper, Hilltopics. C. James Quann, registrar emeritus, wrote the article as one of a series about alumni who gave their lives for their county.

Learn more about the chapel here >

In May 1997, Jeanne's name was inscribed on one of the 25 columns of the Bartholomew County Memorial for Veterans on the lawn of the Bartholomew County Courthouse in Columbus, Indiana. Also inscribed on the memorial is an excerpt from a letter Jeanne had mailed to her mother the morning of the day she was killed.

In May 1998, the restored chapel in a WWII barracks at the Columbus Municipal Airport was named the Jeanne Lewellen Norbeck Memorial Chapel and dedicated to her memory.

In June 1999, Washington State university featured an article about Jeanne in its paper, Hilltopics. C. James Quann, registrar emeritus, wrote the article as one of a series about alumni who gave their lives for their county.

Learn more about the chapel here >

This photograph of Jeanne Lewellen Norbeck was carried in this leather photo case by her husband Edward Norbeck. The date on the back of the photo is May 17, 1943. Seth Norbeck of Santa Fe New Mexico donated these artifacts to the museum. Seth is Edward's son. Under the picture in this leather photograph case Edward Norbeck kept newspaper clippings of news stories of his wife's death in the plane crash, shown below. Edward had this case in his possession until his death at age 75.

Jeanne Lewellen Norbeck November 14, 1912 to October 16, 1944

The coin is tossed to see who gets the BT-13 and who gets the AT-6. Jeanne gets to check out the BT-13. Marybelle Lyall Arduengo gets the AT-6 to test. The Form 1-A reports that the "heavy" left wing is in rig now. Jeanne takes off and puts the plane through its paces in the test area south of Shaw Field. She decides to return to the field. She slows the plane as she enters the landing pattern. Then without warning the left wing drops and the plane flips over and spins into the ground. There was no way to recover at the low altitude for landing. As with all WASP deaths, there was no military escort, and no flag for the coffin authorized by the Army Air Force, as the WASP were Civil Service. The people at the air base chipped in to cover the expenses and the base commander made it possible for an officer to escort her home. Even though it was not authorized, the army officer brought a flag with him to drape her coffin. The family still has the flag.

Jeanne was born in Columbus, Indiana, and grew up there with her brother and sister. She started flying while in high school. In 1933 she graduated from Washington State College with a B. A. in English. Jeanne and her husband, Edward Norbeck, were in Honolulu when Pearl Harbor was bombed. She was an honors student and Group Commander for her WASP training class.

Jeanne was born in Columbus, Indiana, and grew up there with her brother and sister. She started flying while in high school. In 1933 she graduated from Washington State College with a B. A. in English. Jeanne and her husband, Edward Norbeck, were in Honolulu when Pearl Harbor was bombed. She was an honors student and Group Commander for her WASP training class.

about Edward Norbeck, Jeanne's Husband

After Jeanne Lewellen Norbeck's funeral in October 1944, her husband Edward had to leave the next day for Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri to continue his Army Intelligence training program. After some correspondence with Edward for a few months after the funeral, Jeanne's family lost all contact with him. In late 1945, attempts to learn of his whereabouts and if he had survived World War II were unsuccessful. Fifty years later, in 1995, some veteran's information websites were contacted and the Internet was searched for information about Edward, again without success. it appeared that Edward Norbeck's life after 1944 would remain a mystery.

Then on the morning of June 28, 2002, Jeanne's nephew answered his telephone and heard a man's voice say, "Hello, does the name Norbeck mean anything to you?" The caller explained that he was Seth Norbeck, Edward's son! Out of curiosity, Seth had entered his last name into his Internet search engine. One response was "Jeanne L. Norbeck" at an "Atterbury-Bakalar Air Museum," which meant nothing to him, but he clicked on the link anyway to check it out.

When Seth examined the museum website he found a reference to the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) and recalled that his father's first wife flew military airplanes during World War II and was killed in a crash. As he scrolled down, looking at photographs of Jeanne and her family, he came to her wedding picture, and there standing next to her was his father! Seth had discovered information about Edward's first wife, Jeanne Lewellen. He phoned the museum to find out more about Jeanne's family and was referred to her nephew.

Seth reported that after his training at Fort Leonard Wood, Edward was sent first to Washington, DC, and then to the University of Michigan for more training. He was then assigned to Army Intelligence in Washington, DC, where he spent the rest of the war translating top-secret Japanese messages that had been intercepted and deciphered by Army code breakers. Many of the messages he worked on were between the Japanese ambassador to Russia and the Japanese military command in Japan. Edward's fluency in Japanese and his insight into Japanese culture enabled him to both translate and interpret the secret message traffic. His work revealed that the allies were winning the war with Japan.

After being released from the service, he returned to the University of Michigan where he completed a B.A. degree in 1948. While he was studying at the University of Michigan, Edward met Margaret, who became his second wife. They had three children, Crosby, Seth, and Hannah.

He remained at the University of Michigan and earned a M.A. Degree in far eastern language and civilization in 1949. In 1952 he earned a Ph.D. degree in anthropology. His specialty was Asian culture. He did post-doctoral work in Japan and held teaching positions at the University of Utah and the University of California, Berkeley.

Edward obtained a professorship and gained tenure at Rice University. He served as chairman of the Department of Anthropology and Dean of Humanities and Social Studies. He was the author or co-author of numerous papers and books and was well known in his field. From tine to time, he continued his studies in Japan and also spent time in Hawaii where he studied post-World War II changes in the lives of employees on large pineapple plantations. He retired from Rice University in 1981. Edward Norbeck died at his home in 1991 at age 75.

Then on the morning of June 28, 2002, Jeanne's nephew answered his telephone and heard a man's voice say, "Hello, does the name Norbeck mean anything to you?" The caller explained that he was Seth Norbeck, Edward's son! Out of curiosity, Seth had entered his last name into his Internet search engine. One response was "Jeanne L. Norbeck" at an "Atterbury-Bakalar Air Museum," which meant nothing to him, but he clicked on the link anyway to check it out.

When Seth examined the museum website he found a reference to the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) and recalled that his father's first wife flew military airplanes during World War II and was killed in a crash. As he scrolled down, looking at photographs of Jeanne and her family, he came to her wedding picture, and there standing next to her was his father! Seth had discovered information about Edward's first wife, Jeanne Lewellen. He phoned the museum to find out more about Jeanne's family and was referred to her nephew.

Seth reported that after his training at Fort Leonard Wood, Edward was sent first to Washington, DC, and then to the University of Michigan for more training. He was then assigned to Army Intelligence in Washington, DC, where he spent the rest of the war translating top-secret Japanese messages that had been intercepted and deciphered by Army code breakers. Many of the messages he worked on were between the Japanese ambassador to Russia and the Japanese military command in Japan. Edward's fluency in Japanese and his insight into Japanese culture enabled him to both translate and interpret the secret message traffic. His work revealed that the allies were winning the war with Japan.

After being released from the service, he returned to the University of Michigan where he completed a B.A. degree in 1948. While he was studying at the University of Michigan, Edward met Margaret, who became his second wife. They had three children, Crosby, Seth, and Hannah.

He remained at the University of Michigan and earned a M.A. Degree in far eastern language and civilization in 1949. In 1952 he earned a Ph.D. degree in anthropology. His specialty was Asian culture. He did post-doctoral work in Japan and held teaching positions at the University of Utah and the University of California, Berkeley.

Edward obtained a professorship and gained tenure at Rice University. He served as chairman of the Department of Anthropology and Dean of Humanities and Social Studies. He was the author or co-author of numerous papers and books and was well known in his field. From tine to time, he continued his studies in Japan and also spent time in Hawaii where he studied post-World War II changes in the lives of employees on large pineapple plantations. He retired from Rice University in 1981. Edward Norbeck died at his home in 1991 at age 75.

The young dead soldiers do not speak

by archibald macleish

The young dead soldiers do not speak.

Nevertheless, they are heard in the still houses:

who has not heard them?

They have a silence that speaks for them at night

and when the clock counts.

They say: We were young. We have died.

Remember us.

They say: We have done what we could

but until it is finished it is not done.

They say: We have given our lives but until it is finished

no one can know what our lives gave.

They say: Our deaths are not ours: they are yours,

they will mean what you make them.

They say: Whether our lives and our deaths were for

peace and a new hope or for nothing we cannot say,

it is you who must say this.

We leave you our deaths. Give them their meaning.

We were young, they say. We have died; remember us.

From Poem Hunter, see original HERE >

Nevertheless, they are heard in the still houses:

who has not heard them?

They have a silence that speaks for them at night

and when the clock counts.

They say: We were young. We have died.

Remember us.

They say: We have done what we could

but until it is finished it is not done.

They say: We have given our lives but until it is finished

no one can know what our lives gave.

They say: Our deaths are not ours: they are yours,

they will mean what you make them.

They say: Whether our lives and our deaths were for

peace and a new hope or for nothing we cannot say,

it is you who must say this.

We leave you our deaths. Give them their meaning.

We were young, they say. We have died; remember us.

From Poem Hunter, see original HERE >

Learn more about women at war HERE >